IFs Philosophy

A number of assumptions underlie the development of IFs. First, issues touching human development systems are growing in scope and scale as human interaction and human impact on the broader environment grow. This does not mean the issues are necessarily becoming more threatening or fundamentally insurmountable than in past eras, but attention to the issues must have a global perspective, as well as local and regional ones.

Second, goals and priorities for human systems are becoming clearer and are more frequently and consistently enunciated. The UN Millennium Summit and the 2002 conference in Johannesburg (UNDP 2003: 1-59) set specific Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for 2015 that include many focusing on the human condition. Such goals increasingly guide a sense of collective human opportunity and responsibility. Also, our ability to measure the human condition relative to these and other goals has improved enormously in recent years with advances in data and measurement.

Third, understanding of the dynamics of human systems is growing rapidly. Understandings of the systems included in the IFs model are remarkably more sophisticated now than they were then.

Fourth, and derivatively, the domain of human choice and action is broadening. The reason for the creation of IFs is to help in thinking about such intervention and its consequences.

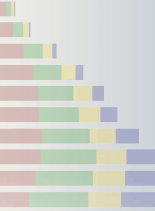

Given the goals of understanding human development systems and investigating the potential for human choice within them, how do we represent such systems in a formal, computer-based model such as IFs? Human systems consist of classes of agents and larger structures within which those agents interact. The structures normally account for a variety of stocks (people, capital, natural resources, knowledge, culture, etc.) and the flows that change those stocks. Agents act on many of the flows, some of which are especially important in changing stock levels (like births, economic production, or technological innovation). Over time agents and the larger structures evolve in processes of mutual influence and determination.

For instance, humans as individuals within households interact in larger demographic systems or structures. In the computer model we want to represent the behavior of households, such as decisions to have children or to emigrate. And we want to represent the larger demographic structures that incorporate the decisions of millions of such households. The typical approach to representing the stocks of such demographic structures is with age-sex cohort distributions, altering those stocks via the flows of births, deaths, and migration. IFs adopts that approach.

Similarly, households, firms, and the government interact in larger economic and socio-economic systems or structures. The model can represent the behavior of households with respect to use of time for employment and leisure, the use of income for consumption and savings, and the specifics of consumption decisions across possible goods and services. It should represent the decisions of firms with respect to re-investment or distribution of earnings. Markets are key structures that integrate such activities, and IFs represents the equilibrating mechanisms of markets in goods and services. Again there are key stocks in the form of capital, labor pools, and accumulated technological capability.

In addition, however, there are many non-market socio-economic interactions. IFs increasingly represents the behavior of governments with respect to search for income and targeting of transfers and expenditures, domestically and across country borders, in interaction with other agents including households, firms, and international financial institutions (IFIs). Social Accounting Matrices (SAMs) are structural forms that integrate representation of non-market based financial transfers among such agents with exchanges in a market system. IFs uses a SAM structure to account for inter-agent flows generally. Financial asset and debt stocks, and not just flows, are also important to maintain as part of this structural system, because they both make possible and motivate behavior of agent-classes.

Further, governments interact with each other in larger inter-state systems that frame the pursuit of security and cooperative interaction. Potential behavioral elements include spending on the military, joining of alliances, or even the development of new institutions. One typical approach to representing such structures is via action-reaction dynamics that are sensitive to power relationships across the actors within them. IFs represents changing power structures, domestic democracy level, and interstate threat.

Still further, human actor classes interact with each other and the broader environment. In so doing, important behavior includes technological innovation and use, as well as resource extraction and emissions release. The structures of IFs within which all of these occur include a mixture of fixed constraints (for instance, stocks of non-renewable resources), uncertain opportunities for technological change in economic processes, and systems of material flows.

In summary, International Futures (IFs) has foundations that rest in (1) classes of agents and their behavior and (2) the structures or systems through which those classes of agents interact. IFs is not agent-based in the sense of models that represent individual micro-agents following rules and generating structures through their behavior. Instead, as indicated, IFs represents both existing macro-agent classes and existing structures (with complex historic path dependencies), attempting to represent some elements of how behavior of those agents can change and how the structures can evolve.

In representing the behavior of agent classes and the structures of systems, IFs draws upon large bodies of insight in many theoretical and modeling literatures. While IFs frequently breaks new ground with respect to specific sub-systems, its strengths lie substantially in the integration and synthesis of bodies of earlier work.